During the years of what many would refer to as ‘doing technical stuff’ in the humanitarian and development sector, my aspiration to work on Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) programmes kept growing. But I lacked the theoretical background to travel down this path.

The part-time, distance-learning MSc Environmental Engineering programme at the University of Strathclyde (Glasgow, Scotland) offered an excellent opportunity to get me started. The programme facilitated a flexible, off campus study mode., which would be essential, since I was about to move with my wife and kids from Belgium to the United Republic of Tanzania. Also, within the department, there was a wealth of experience in WASH through established collaboration with WASH research entities in Malawi.

My priority by 2024 was to graduate with my master’s by October 2024. However, the lingering question of how to enter the world of WASH research after graduation came more and more to the forefront. By then, the NIHR-funded project to improve adolescent health and wellbeing in Malawi had already started. The project, a collaboration between my university, Kamuzu University of Health Sciences, and Malawi University of Business and Applied Sciences, looked like a great opportunity for me. WASH was one of the three key areas of focus. The team was very diverse, and to evaluate change, data was collected annually for three years. I wanted to join this project, anticipating its significant impact. Also, it provided valuable capacity building and training opportunities. Finally, I was delighted to be offered a PhD within the project.

And suddenly, by October 2024, I was part of the NIHR funded Global Health Research Group on Adolescents Health and Wellbeing. Besides WASH, the project has two other main focusses, Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) and Well-being, and consists of an excellent blend of postgraduate and senior researchers, who had already commenced with data collections. I was researching fully remotely from Tanzania, physically isolated from my colleagues based in either Glasgow (Scotland) or Blantyre (Malawi). What was I going to do? How would I fit in?

I had little time to think about it. A short, pre-planned vacation two weeks into my PhD program felt awkward to me, but was not a problem at all for my supervisor: ‘you organise your own plans and you do what you see fit’. I loved the autonomy but also felt the individual responsibility. Before the end of October, my supervisor informed me about a funding opportunity focused on the career development of researchers in their early stages. I was enthusiast, but suddenly also mildly uneasy. It was my first grant application. I found it difficult to select a suitable topic, let alone to turn the topic into a project proposal, respecting the award scope. On top of that, the grant’s scope required collaboration and mentorship from global health researchers external to my project team. Luckily, I could rely on excellent support from my supervisors and a colleague that was successful in getting the grant in a previous round. I established a collaboration with two senior global health researchers. My supervisors helped me connect with an environmental health expert, while I independently reached out to and connected with a behavioural science expert. A few emails and meetings later, the enormous challenge was writing a proposal that respected the grant’s strict word limit. The commitment of everyone involved allowed me to apply on time. Months later, feedback from the grant reviewers followed. My application felt out of the grant envelope. I was unsuccessful. However, the feedback confirmed my proposal was good with some minor suggestions for improvement. I learned how competitive these grants are, and how being unsuccessful in obtaining grant applications is part of research. Despite some disappointment, I enjoyed the application process. It proved beneficial, guiding my research towards behavioural change science and facilitating connections with experts in the field.

Throughout this period, project activities continued, identifying the most pertinent WASH issues through intensive collaboration with adolescents and their communities in Malawi. Among them, inadequate access to water points in schools, poor latrine use both in and out-of-school, and low adherence to good hand hygiene practices. To respond, the team was designing targeted interventions, one for each issue. That is where I saw an opportunity to jump in. I aim to investigate how these issues are linked with each other, how they influence each other. I will also bring in insights from our colleagues in the SRH and wellbeing work strands to map how WASH influence the SRH and wellbeing of adolescents in Malawi.

In parallel to writing my first grant proposal and integrating in the project, I also attended several short workshops, and some longer online training courses. These activities directly related to my research topic, while some focussed on developing transversal research skills. While that might sound a bit at random, the university has a framework in place allowing you to work towards an award, a credited postgraduate research certificate. Every meaningful activity I undertake is credited if matched with any of the diverse learning outcomes within the framework. Five different competence areas categorise the many learning outcomes. Over the course of the doctoral degree, I must earn sufficient credits for each competence area. I find the framework supportive of my development. Gradually, I will work my way towards the award, ultimately towards becoming a well-rounded early career researcher.

One of the longer online trainings I was accepted to join was the ‘Publishing and Funding Your Global Health Research’ training developed by the International Network for the Availability of Scientific Publications as part of its AuthorAid project. The training was well-organised and feature great content. It was one of the most engaging, interactive online trainings I have completed so far, even though there were no group assignments. I had to keep up the pace every week to go through the asynchronous study materials to be prepared for the frequent live sessions. You better come prepared for these sessions. A diverse panel of senior global health researchers was available for questions. And I had many: ‘Why would I ever consider publishing in subscription-based journal rather than open-access journals?’, ‘When writing to convince a grant reviewer about the expected impact of my project proposal, how to strike the balance between a powerful but humble impact statement?’ and so forth. Whenever participants were not engaging, the panel members prompted challenging questions, provoking thought on the content covered in the learning materials. Never a dull moment. Besides that, three assignments gave the opportunity to put the learning into practice. We had to write a research abstract, a reflective essay on research ethics, and prepare a short grant proposal. It did not stop there. Once submitted, each participant had to review three assignments of their peers. An insightful experience to take both the role as writer and reviewer. I regret that this training started after the deadline for my first grant application. Would I have succeeded with earlier training? Maybe, maybe not. The training emphasized that securing research funding demands persistence, and that success involves learning from and accepting inevitable failures.

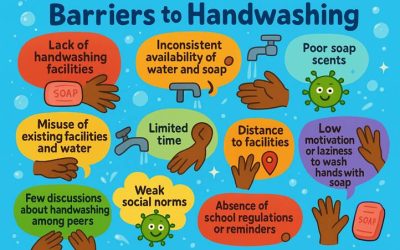

Another intense activity I completed was an interactive, nine-week online training on developing and sustaining Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) programmes in schools, referred to as the WinS programmes. This course was created by the Centre for Global Safe WASH at Emory University in partnership with UNICEF. One useful tool I learned about was the “Problem Tree” (see Figure 1a), a participatory approach that helps identify the root causes of a WASH problem by involving all stakeholders. In our training groups, we acted as stakeholders and chose a WASH problem to analyse. The problem itself is like the trunk of a tree, with visible consequences as branches. We then explored the underlying causes represented by the roots. By finding common causes, we pinpointed the root cause(s), which can guide effective interventions. Further, we also learned how to develop a behaviour change intervention with the help of a behaviour change toolkit (see Figure 1b) and learned how to use a logical framework to assess and represent the logic behind the purpose and activities of a WASH project (see Figure 1c).

I am an engineer passionate about water pumps and other ‘technical stuff’. However, I realise we cannot solve global health issues by installing infrastructure alone. For example, installing a fabulous handwashing station alone will not solve inadequate hand hygiene practices. To get people to practice empirically proven good behaviours, we need to understand how to change their behaviour. I had some more reading to do. Well versed in using scientific databases, I quickly discovered a review article reporting on the effectiveness of Behavioural Change Techniques (BCT) used in hand hygiene interventions. The method section revealed how the authors used an internationally supported taxonomy to code the BCTs found in the included studies. This led me to Behaviour Change Techniques Taxonomy Training developed by the University College London. Module by module, the online training introduced me to new BCTs. You must complete exercise sets to access the next model. I had to code excerpts from real intervention descriptions that deliver a BCT. It was an intense and insightful training. After exercises covering the 93 BCTs, I see them being used all around me. It further triggered my interest in literature focusing on the non-physical elements of WASH systems (i.e., WASH software), the complementary component of WASH hardware (e.g., a pit latrine). By now, my pile of books on WASH software is readily catching up on the pile of books on WASH engineering.

A bit overwhelmed by my first few months, new insights, and the new science fields that shape my research, the engineer in me felt the need of a systematic way forward. My master’s dissertation introduced me to ‘Systems Thinking’ principles. It is an approach used to manage complex systems. It allows exploration of the causality and interrelation of components to a system that collectively lead to desired or undesired outcomes. In my case, how do Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene drive or form barriers to the health and wellbeing of adolescents in Malawi? The WASH reality of adolescents being the complex system, the status of the health and wellbeing of adolescents being the outcome we wish to understand. Ultimately, to improve the health and wellbeing of adolescents, I aim to model how change impacts the outcome of the complex dynamic system. A Causal Loop Diagram is the tool to do this. Analysis of our rich data sets will identify model variables and features, revealing WASH-related drivers and barriers to adolescent health and wellbeing in Malawi. The longitudinal feature of the data sets will help to quantify the interactions of the model variables and feedback mechanisms to simulate the change in the system’s state over time. I expect the model to reveal dynamic complexities such as delays, feedback effects, and unintended consequences not immediately visible in static analysis. It will complement the team’s qualitative and statistical analysis.

I can conclude that I enjoyed the challenging start and quickly integrated into the project, thanks to the welcoming team. Recently, my family and I moved from Tanzania to the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire (Figure 2), embracing a new environment filled with fresh challenges and exciting opportunities. Despite these changes, my commitment remains as strong as ever. I look forward to updating you in a few months on the progress and evolution of my research.

By Jasper Ceuppens – Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering at University of Strathclyde (Glasgow, Scotland)