As easy as promoting handwashing with soap at critical times (e.g. after using the toilet) may seem, it remains a challenge in both schools and households in low income settings. In Malawi, the practice among different population groups is still low, for example, with adolescents, who spend most of their time in school, our formative research has shown that less than 1% of observed handwashing opportunities included the use of soap. Using the COM-B (Capabilities, Opportunities, and Motivation) behaviour change approach to identify handwashing with soap barriers and facilitators, we found that while adolescents have the capability to wash hands with soap, there are many barriers (Figure 1) to both opportunity and motivation that limit consistent practice.

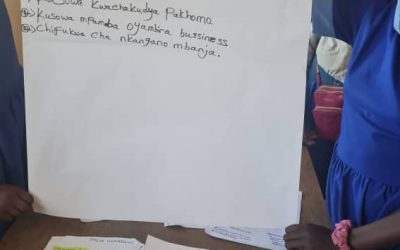

Figure 1: Barriers to handwashing with soap at critical times

Although commendable efforts are being made by various stakeholders, some challenges continue to persist. As such, we are trying a different approach, to co-develop, with the adolescents, a participatory hand hygiene intervention for schools aimed at sustained handwashing with soap practice. The intervention will be tested through a feasibility study before scaling up recommendations are made. Along the journey, we paused, we kept asking ourselves: what’s missing in existing hand hygiene efforts? That’s why we spent time with a school in rural Mchinji, conducting short experiments with the learners to test what would make handwashing easier, more appealing and consistent before incorporating these insights into the intervention. We tested soap types, soap dispensing methods, the amount of water used per wash, and asked questions of the learners, and observed their current water reservoir refilling approach.

Figure 2: Water used for handwashing with soap by one learner being measured

Figure 3: Sets of handwashing facilities with different soap brands ready for soap preference handwashing with soap experiments

Figure 4: A learner testing the soap dispensing methods provided

Working closely with students and teachers, the short experiments showed practical insights into handwashing behaviours and preferences. For the tested different soap brands (Figure 4), lather, scent, and colour were identified as the most important attributes, with the brands Butex and Azam emerging as the preferred choices, even after participants were made aware of prices, for example Butex has a higher cost. Various soap dispensing methods were trialed, with ‘soapy water’ and ‘soap in a bag’ rated easiest to use and producing the best lather. Observations of 48 handwashing tests with adolescents were also conducted to assess the amount of water used (Figure 2) and we found that on average 314ml of water was used per handwash per adolescent, with adolescent boys using more water (337 ml) than adolescent girls (286 ml). We also explored their perceptions on potential nudges to encourage handwashing to be included in the interventions, such as painted footprints leading to the handwashing facility, handprints on water dispensers, posters, and stickers to encourage handwashing at critical times. Participants generally understood and responded positively to these cues, though they indicated that some required orientation and highlighted challenges such as vandalism, limited maintenance materials, and durability. Finally, we explored refilling of handwashing water reservoirs in the school which is usually done by learners using a mix of duty rosters, random selection, voluntary efforts, or as a form of punishment. Water for refilling is sourced from the borehole within the school premise, where 20 litres buckets are used to fetch and carry the water to the handwashing facilities. From their narration and observations made during one school day, out of the seven observed handwashing buckets with taps, three were refilled twice, while the rest still had enough water.

But we haven’t stopped there, building on the findings from these tests we have just started implementing a Trial of Improved Practices (TIPs) which will expose the learners to some aspects of the interventions for a period of 2 weeks. We will then gather feedback on practicality, acceptability and potential sustainability through observations & Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) with the learners and staff. These co-design activities and findings will support us to produce a participatory, evidence-based hand hygiene intervention that considers adolescents’ preferences, practical constraints, and motivational cues, bringing us closer to sustainable handwashing practice among adolescents and making “our future is at hand” a reality.

By Rossanie Malolo (PhD Student) ~ Malawi University of Business and Applied Sciences